🌍 Earth Hazards ⚡

How Geophysics Helps Us Understand Our Changing Planet

EARTH HAZARDS

Earth hazards occur daily across the globe, and in the U.S. lead to billions of dollars of damage and loss each year. Scientists use instruments both to monitor for immediate hazards and to better understand these events, with the aim of forecasting them well in advance. Geophysical instruments such as seismometers, high-precision GPS, and satellites are among the tools used to study these hazards to protect life and property.

AVALANCHE

Two factors contribute to triggering an avalanche: how much liquid water is in the snow and how thick the snow layer is compared to the mountain slope on which it sits. Seismic instruments, GPS, and upward-facing radar dishes installed before snowfall can help detect avalanches. Radar gauges snow height, while interference of the GPS signal provides information on liquid water content, and seismometers detect snow movement. Avalanche detection using seismic and geodetic data can provide reliable data avalanche forecasting.

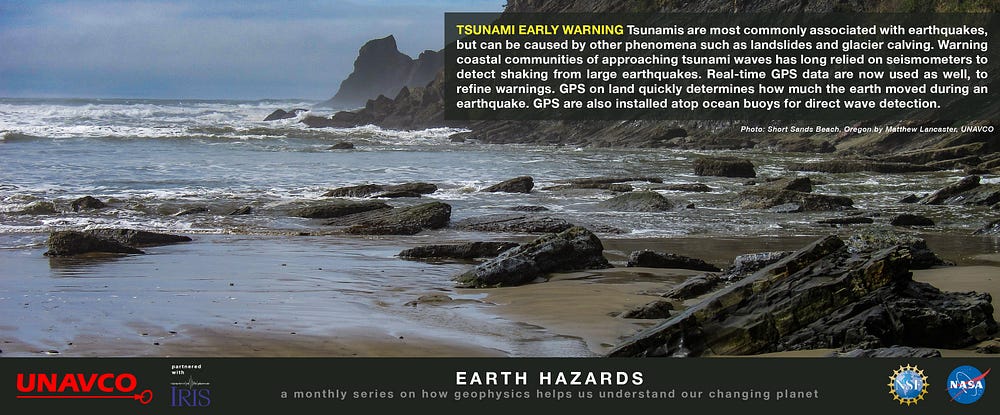

TSUNAMI EARLY WARNING

Tsunamis are most commonly associated with earthquakes, but can be caused by other phenomena such as landslides and glacier calving. Warning coastal communities of approaching tsunami waves has long relied on seismometers to detect shaking from large earthquakes. Real-time GPS data are now used as well, to refine warnings. GPS on land quickly determines how much the earth moved during an earthquake. GPS are also installed atop ocean buoys for direct wave detection.

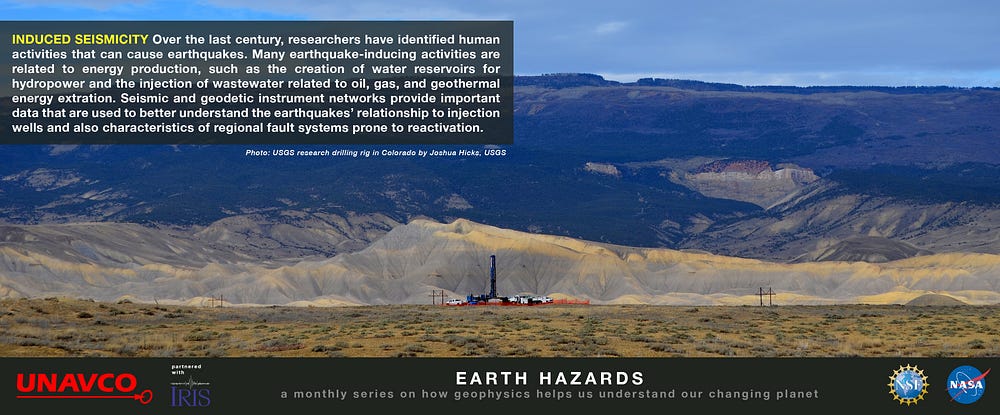

INDUCED SEISMICITY

Over the last century, researchers have identified human activities that can cause earthquakes. Many earthquake-inducing activities are related to energy production, such as the creation of water reservoirs for hydropower and the injection of wastewater related to oil, gas, and geothermal energy extraction. Seismic and geodetic instrument networks provide important data that are used to better understand the earthquakes’ relationship to injection wells and also characteristics of regional fault systems prone to reactivation.

SOLAR STORMS

Solar Wind, a flow of charged particles released from our Sun, constantly bombards Earth. Sometimes, coronal mass ejections from the Sun send massive amounts of charged particles to our planet, resulting in geomagnetic storms that can interfere with power grids and navigation systems. Satellite, magneto telluric, and GPS observations monitor strong fluctuations in Earth’s electric and magnetic fields, helping us protect Vital infrastructure.

LANDSLIDES

Landslides have the potential to occur almost anywhere there is a steep slope, and can cause billions of dollars’ worth of damage. Seismic instruments capture important information about landslide initiation and propagation, while geodetic techniques capture landform changes. These data help scientists better understand how landslides occur, and aid in preparation and recovery.

COASTAL EROSION

The erosion of shorelines by high Wind, rain, and tidal currents impacts coastal communities worldwide. Scientists track how the coastal landscape is changing through satellite-based and ground-based lidar techniques, helping communities adapt to increasingly common coastal hazards such as storm surge. Scientists can also predict erosion rates using past observations and forecast future erosion, allowing communities to better plan.

LOCAL GROUND SHAKING

During an earthquake, not all ground shakes alike. Geophysical and geological studies can determine a specific site’s response to seismic waves, as well as susceptibility to secondary hazards like landslides, flooding, and liquefaction. Also called seismic microzonation, these studies are being increasingly incorporated into the development of building codes to mitigate damage in populated earthquake-prone areas.

SLOW EARTHQUAKES

Episodic tremor and slip (ETS) is a recently discovered fault behaviour in regions of known large earthquakes. During ETS, slip along the fault is very small and slow, resulting in a Low rumble that can last several weeks and be picked up by seismometers but not felt by humans. ETS was first discovered in GPS data in the Pacific Northwest, which showed a temporary change in station direction about every 14 months. Studying ETS is important for our understanding of the hazards of major faults.

THAWING PERMAFROST

Permafrost is a shallow layer of soil and rock in the ground that is frozen year-round. Located in high latitudes or at high elevations, melt occurs as these regions slowly warm due to changing climate. Ground that was once frozen is becoming unstable, causing buildings and roads to slump, tilt, or crack. Remote sensing techniques help scientists determine the thickness of permafrost over broad regions.

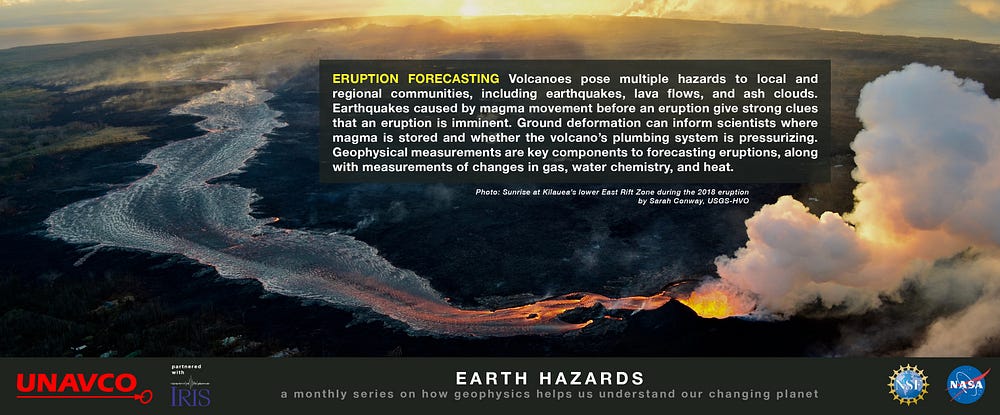

by Sarah Conway, USGS-HVO

ERUPTION FORECASTING

Volcanoes pose multiple hazards to local and regional communities, including earthquakes, lava flows, and ash clouds. Earthquakes caused by magma movement before an eruption give strong clues that an eruption is imminent. Ground deformation can inform scientists where magma is stored and whether the volcano’s plumbing system is pressurizing. Geophysical measurements are key components to forecasting eruptions, along with measurements of changes in gas, water chemistry, and heat.

GLACIER CALVING

Large chunks of ice break off the edge of glaciers in a process known as glacier calving. In a warming climate, these events can accelerate and increase the risk of hazards. Glaciers calving into the ocean create large, dangerous waves. Scientists can use seismic and even underwater acoustic techniques to monitor calving events. The ice mass and speed of glaciers can be measured through remote sensing and ground-based GPS.

Source: unavco.org